Ligament Tears

What are ligament tears?

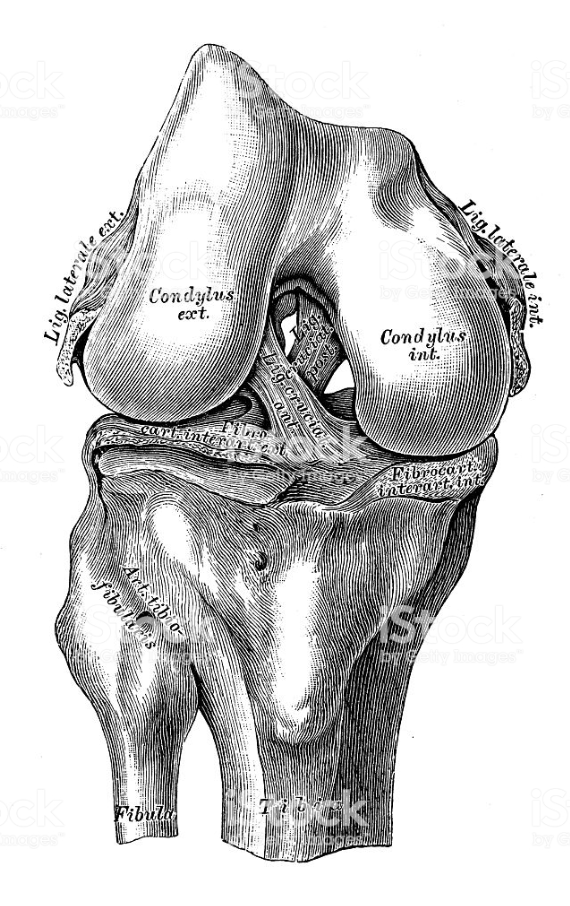

There are 4 main ligaments (tough bands of tissue) in the knee which connect the thigh (femur) to the shinbone (tibia). The medial and lateral collateral ligaments (known as MCL and LCL), stop the knee from sliding sideways, and can be found one on each side of the knee. The anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments (known as ACL and PCL) which cross to form an “X” on the inside of the knee, beneath the kneecap, stop the knee from sliding backwards or forwards over the tibia. If you make a movement which stretches these ligaments too far they can tear – either partially or completely – which happens usually during sporting activity. The most common tear is an ACL tear, which is often seen with a MCL tear, whilst a PCL tear is reasonably rare. Damage to these ligaments will result in instability in the knee joint which can lead eventually to other problems, such as meniscus tears, cartilage damage and osteoarthritis.

What causes them?

The ACL can be torn either by a blow to the outside of the knee, or by any action that causes the femur to move too far forwards over the tibia e.g. a sudden deceleration or change of direction, twisting, pivoting, landing from a jump. These movements are common in many sports such as football, basketball, tennis etc. Due to the different structure of women’s leg bones, and the way their muscles and tendons work, they are more at risk of ACL tears than men.

The PCL can become torn if the tibia moves too far backwards under the femur, and normally occurs when the knee receives a blow from the front e.g. during a fall or car accident.

The collateral ligaments become torn when the tibia is forced too far sideways (either medially i.e. towards the other knee, or laterally i.e. outwards), due to a blow, sudden twisting or during sports such as football or ski-ing.

Any, or all, of the ligaments can be damaged if the knee is hyper-extended i.e. snapped back to far.

How does it feel?

Some patients hear a ‘popping’ noise when the ligament is torn. Within hours of the incident, the knee will become swollen and stiff and it will be difficult to straighten your leg. It is especially painful if you put weight on the leg, and so walking can be a problem. With a PCL tear the swelling is normally less, although the joint will still feel stiff and painful. After a week or so, the initial pain and stiffness will subside although you may be left with a feeling of instability, as if the knee may give way.

With chronic (i.e. long-term) injuries the knee may even give way at times, and if you have used your knee a lot it can start hurting. Walking downhill or on slippery surfaces can be particularly difficult, and you may feel as if you can’t trust your knee to hold your bodyweight.

Diagnosis

A physical examination will give a very good indication of which knee ligaments have been damaged . Your doctor will carry out ‘stress tests’ on your knee which involve moving your leg into various positions and then applying force to see whether your knee resists or gives way. He may ask you to have an X-ray of your knee to rule out any bone fractures. If there is any doubt, the doctor will prescribe an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan which is the surest way of showing a ligament and a, frequently associated, meniscal tear MRI allows also to rule out a bone bruise (a lesion due to the impact on the bone) which, if present, may suggest a different treatment.

Treatment – conservative

Immediately after tearing a ligament your doctor will prescribe rest, the application of ice-packs, anti-inflammatories and sometimes crutches to help walking. If the knee is particularly swollen your doctor may “aspirate” or remove the liquid from your knee to help you regain movement in your knee. If there is blood in this liquid, it is a clear sign that a ligament has been torn. Once the pain and swelling have subsided, your doctor will give you a programme of exercises to strengthen your leg muscles – particularly the quadriceps in your thigh – in order to compensate for any knee instability. You may find an elastic knee support or knee brace helpful during everyday activity.

If the pain, swelling and instability do not disappear over time, you need to return to your doctor and surgery may be necessary.

Treatment – surgical

Arthroscopic Ligament Replacement: your surgeon will replace the torn ligament with a piece of substitute tissue, either from your own knee, or in rare cases, from a donor. If the surgeon decides to substitute the ligament with a tendon from your own knee (called an autograft), he will either use a piece from the centre of your patellar tendon or from your quadriceps tendon, or he will use one of the flexor tendons that run up the inside of the thigh (either the gracilis or the semitendinosus tendons). This graft acts as a “scaffold” inside which a new ligament will form, and eventually the grafted tissue will dissolve. The removal of any of these tissues will not affect the eventual strength or functionality of your leg.

In arthroscopic surgery, your surgeon will first make two small access holes in your knee and through them remove the damaged pieces of ligament. Then he will make a small incision at the top of your shin and remove the tendon that is being used for the reconstruction. Next, he will drill a hole in the tibia and the femur, into which he will thread the ends of the new ligament, so that it runs between the two bones exactly as your old ACL did. Each end is held in place with a screw or staple. Your surgeon will then close the wounds with stitches. To stop excess fluid building up in your knee, your surgeon will insert a small tube through a tiny incision above your knee, which will be removed after 1-2 days.

Rehabilitation after surgery

After your operation your doctor may request that you are put on a CPM machine (continuous passive movement) which slowly bends and straightens your leg whilst you lie in bed, to avoid the joint stiffening up. Otherwise you will be given very light exercises to do to get the leg moving again. You will need to walk with crutches for the first 4-6 weeks, gradually increasing the amount of weight you put on your operated leg.

After a ligament replacement you will need to follow a specific programme of physiotherapy treatments (normally for about 3-4 months) in order to regain the full strength and functionality of your leg, whilst protecting the new ligament from damage. The first physiotherapy treatments will aim to help control the pain and swelling from the surgery, and will gradually become more strenuous as you rebuild your muscles and regain movement and co-ordination. During this period you will need to go back to your surgeon for regular check-ups, so he can monitor your progress.

When will I be back to normal?

Ideally you should be able to return to your previous activities: driving should be possible as soon as the wounds have healed (after about 2 weeks), whereas you will be able to return to physical activity when you have regained full knee movement and your knee no longer swells. Office workers can return to work on crutches after 1-2 weeks, whilst manual workers may need to wait up to 6 weeks. However, athletes are usually advised to wait at least 6 months before returning to their sport, and in some cases they may not be able to compete at their previous level.