Cartilage Damage

What is cartilage damage ?

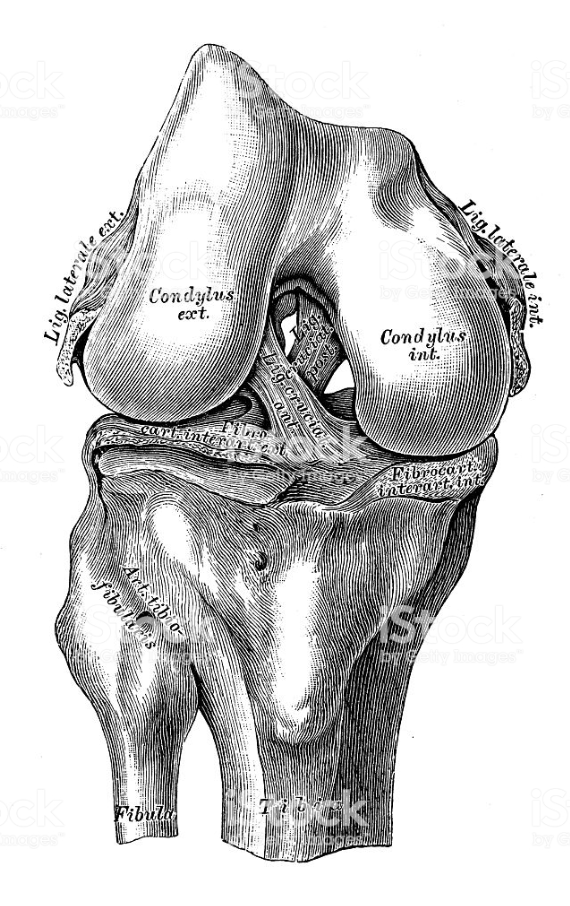

Articular cartilage is the hard, slippery ‘gristle’ that covers the ends of the thighbone, shinbone and the back of the kneecap that allows the surfaces to move smoothly and efficiently against each other during movement. When the cartilage is damaged, a so-called lesion (often a tear or a pit) appears in the surface. There are different grades of lesion (the usual grades are from 1 to 4), and if a tear goes all the way through the cartilage to the bone, it is called a full-thickness lesion. Once torn or damaged, fragments of the cartilage may break off causing further damage to the joint surfaces, or the damaged surface itself may cause catching and locking.

As there is no supply of blood or lymph vessels to the cartilage, it lacks the ability to repair itself naturally, although in the case of a full-thickness lesion the blood supply from inside the bone may sometimes start some healing inside the lesion forming fibrocartilage. This is a tough, dense, fibrous material that helps fill in the lesion, although it is by no means an ideal replacement for the very strong, smooth articular cartilage that previously covered the bone surface.

What causes it?

It can be torn by a bad fall, slow damage after a knee injury, general wear and tear or poor blood supply to the joint.

How does it feel?

When the surface of the cartilage is damaged, it is usually not painful at first. However, any holes or rough spots in the cartilage can disturb the complex balance of the joint causing inflammation and pain, and the feeling of catching or locking can make normal activity difficult. With a full-thickness lesion, the pressure and strain on the bare portion of bone can also become a source of pain. Finally, if the cartilage injury isn’t treated, it may eventually cause osteoarthritis.

Diagnosis

The case history and physical exam are usually enough to make a diagnosis. X-rays are taken to rule out fractures and an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan may be used to confirm the damage.

Treatment – conservative

Your doctor may recommend ways to manage the symptoms such as applying ice, anti-inflammatory medication and physiotherapy. In some cases a knee brace or shoe orthotic (insole) may improve knee alignment, thus easing pressure on the affected knee.

Treatment – surgical

1. Arthroscopic Debridement: this is carried out on less damaged areas and is aimed at preventing or delaying further progression of the problem. This procedure is usually used when the lesion is too large for a grafting type procedure or the patient is older and an artificial knee is planned for the future. The surgeon cleans up the joint, trimming rough edges of cartilage and removing loose fragments. Sometimes this procedure is referred to as chondroplasty. It is only intended to be a short-term solution, but it is often successful in relieving symptoms for a few years.

2. Bone Marrow Stimulation Procedures: abrasion arthroplasty and arthroscopic microfracture are two procedures that are performed to stimulate the bone marrow, making it form scar tissue or ‘fibrocartilage’, which replaces the damaged articular cartilage:

- Abrasion Arthroplasty – when the cartilage has worn away and bone rubs on bone, the bone-surface becomes hard and shiny. During arthroscopy the surgeon can use a special instrument known as a burr to scrape off the hard, polished bone tissue from the surface of the joint. The scraping action causes a healing response in the bone, with new blood vessels entering the area, bringing stem cells, and causing the formation of fibrocartilage. The fibrocartilage that forms may not remove all the symptoms of pain in the knee, and therefore this may be only a temporary solution.

- Arthroscopic Microfracture – the surgeon will clear away the damaged cartilage, and then use a blunt tool arthroscopically to poke a few tiny holes in the bone under the cartilage. Like abrasion arthroplasty, this procedure is used to get the layer of bone under the cartilage to produce a healing response, triggering the formation of new cartilage (mainly fibrocartilage) inside the lesion.

3. Osteochondral Graft: during either arthroscopic or open surgery, the surgeon removes a cylinder of bone tissue which contains the damaged bone and cartilage from the site of the lesion. Then a cylinder of undamaged bone and cartilage, of exactly the same size, is removed from elsewhere in the knee (from a non weight-bearing site). This cylinder is the either glued or press-fitted into the original site of the lesion.

4. Chondrocyte Transplant (cartilage graft): during arthroscopy the surgeon will remove a piece of healthy cartilage, which will then be put in culture. Over the next 4-6 weeks more cartilage cells will grow. These cells will then be re-injected into the lesion where they should adhere and replicate, creating new articular (not fibro) cartilage.

Rehabilitation after surgery

Debridement: your surgeon will instruct you to place a comfortable amount of weight on your operated leg using crutches, and to increase the weight on your operated leg until you can walk normally.

Bone marrow stimulation procedures/Osteochondral graft/Chondrocyte transplant – if the operation is performed on a weight-bearing part of the knee, you will have to use crutches for at least 8-12 weeks to allow the new cartilage to develop properly. If the operation is on the back of the kneecap or the adjoining bone, you will be able to walk normally but will have to avoid putting any pressure through a bent knee (i.e. going up and down stairs, walking on steep slopes, squatting etc) for 6-8 weeks. You will start physiotherapy immediately after the operation, with the first treatments designed to help control the pain and swelling from the surgery, and to make sure you are only putting a safe amount of weight on the affected leg. Then exercises will be introduced to help improve knee motion and to get the muscles toned and active again. At first, emphasis is placed on exercising the knee in movements that don’t strain the healing part of the cartilage. But as the program evolves, more strenuous exercises will be introduced.

When will I be back to normal?

Ideally, patients will be able to resume their previous lifestyle activities. Some patients may be encouraged to modify their choice of activity.

Debridement: return to normal activity will depend on how much discomfort and swelling you experience. These are not usually severe and, if you were quite fit before surgery, you could be back to normal in a few weeks, and driving within 4-5 days of the operation.

Osteochondral graft: the recovery period after this procedure is variable depending upon the size, position and severity of the lesion being treated. However, most heal up over a 6-8 week period, with driving permitted after 15 days.

Bone marrow stimulation procedures/Chondrocyte transplant: It could be 9-12 weeks before everyday activities become completely comfortable, although you can start driving after 15 days. The damaged area goes on developing for months after surgery, so certain sports may not be advisable during that period.