Hip osteoarthritis

What is hip osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis is a disease where the smooth articular cartilage coating the ends of the bone in a joint becomes damaged or worn away, exposing the underlying bone. The exposed bone then becomes diseased and deformed causing inflammation and severe pain. Small outgrowths, called bone spurs or osteophytes, may form on the bone surfaces and block movement or damage the soft tissues. Arthritis occurs most commonly in the weight-bearing joints (knee, hip) that suffer the heaviest wear and tear, however it is also seen in other joints of the body. As it is a degenerative disease, it is most commonly seen in older patients (60 years plus).

What causes it?

Previous hip injuries, such as fractures or dislocations, can lead to osteoarthritis, as the cartilage may have been damaged in the trauma, or the joint is no longer properly aligned and wears unevenly.

Osteonecrosis causes an area of the femoral head to degenerate, and can lead to the rest of the bone becoming damaged by arthritis.

As women are more likely to suffer from dysplasia (a congenital malformation of the hip), osteoarthritis is more common in women than in men.

How does it feel?

You will have pain in your groin that may reach out into your buttock, and down the front and side of your thigh. The pain will increase when you stand or walk for a long time. In the later stages, the pain will be constant and may stop you sleeping, and the joint will stiffen and you may be unable to rotate or extend your leg.

Diagnosis

Your doctor will ask you about your medical history (particularly about any previous hip injuries) and will give you a physical examination. He will ask for X-rays, which will show a narrowing of the space between the bones if you have arthritis, and will show any pits in the bone surface and/or bone spurs. He may also ask for an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan, as initially, when there is mainly only cartilage damage, this test can show the condition of the cartilage.

Treatment – conservative

Your doctor may prescribe any, or all, of the following treatments:

- Change of lifestyle – for example losing weight, and regulating your level of activity

- Medication – chondro-protective (e.g. glucosamine, chondratin sulphate, or methyl methanesulfurnate), or anti-inflammatory medication

- Injection therapies such as hyaluronic acid injections

- Electrical stimulation therapies, shock wave therapy and magnetotherapy

- Physiotherapy – exercises to regain the range of movement of your leg, your balance, and to rebuild the muscles.

Treatment – surgical

Arthroscopic Debridement: this is carried out on less damaged areas and is aimed at preventing or delaying further progression of the problem. This procedure is used when the patient is older and an artificial hip is planned for the future. The surgeon cleans up the joint, trimming any rough edges of cartilage, and removing loose particles. It is only intended to be a short-term solution, but it is often successful in relieving symptoms for a few years.

Bone Marrow Stimulation Procedures: abrasion arthroplasty and arthroscopic microfracture are two procedures that are performed to stimulate the bone marrow, making it form scar tissue or ‘fibrocartilage’, which replaces the damaged articular cartilage:

Abrasion Arthroplasty: when the cartilage has worn away and bone rubs on bone, the bone-surface becomes hard and shiny. During arthroscopy, the surgeon can use a special instrument known as a burr to scrape off the hard, polished bone tissue from the surface of the joint. The scraping action causes a healing response in the bone, with new blood vessels entering the area, bringing stem cells, and causing the formation of fibrocartilage.

Arthroscopic Microfracture: the surgeon will clear away the damaged cartilage, and then use a blunt tool to poke a few tiny holes in the bone under the cartilage. Like abrasion arthroplasty this procedure is used to get the layer of bone under the cartilage to produce a healing response, triggering the formation of new cartilage (mainly fibrocartilage) inside the lesion.

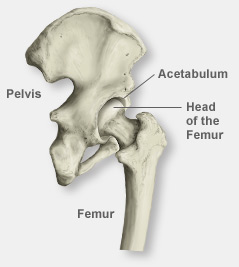

Total Hip Replacement: a hip prosthesis is made up of 2 parts: the acetabular component which replaces the socket, made of a metal cup lined with a plastic or ceramic liner; and the femoral component which is a metal ball and stem (or sometimes a ceramic ball and metal stem), and replaces the femoral head.

The surgeon will make a 10-12cm incision on the outside of the hip. Then he will shape the acetabulum to fit the socket-shaped acetabular component, removing all the damaged cartilage and bone. Next he will remove the femoral head, and make a tunnel down the femur to house the stem of the femoral component. He will then fit the components into place, fixing them with bone cement if he is using a cemented prosthesis. Your surgeon will then align the joint and ensure that the leg rotates and moves correctly. After surgery, you should have a correctly aligned hip and a full range of motion.

In some patients the arthritis may have affected only the femoral head and so your surgeon will only replace the femoral head or resurface it:

Hemiarthroplasty: the surgeon will make a 10-12cm incision on the outside of the hip, through which he will remove the femoral head, and make a tunnel down the femur to house the stem of the femoral component. He will then fit the new femoral implant into place, fixing it with bone cement if he is using a cemented prosthesis, or pressure fitting it if he is using an uncemented prosthesis. Your surgeon will then move the new femoral implant back into the acetabulum socket, ensuring that the leg rotates and moves correctly.

Femoral Resurfacing: your surgeon will make a 10-12cm lateral incision through which he will smooth and shape the femoral head, and the acetabulum so that they are the right shape to fit the artificial hip components. He will then place a metal cover or cap over the top of the femoral head, fixing it with bone cement, and fix the acetabular component into the acetabulum. Again, this procedure is used for younger patients.

In order to increase the life of your new hip you must maintain an appropriate weight for your height, develop good muscle tone and avoid activities that will put strain on the hip joint.

Revisions

In the unlikely event that there are problems with your hip replacement (pain in the joint, swelling, reduced movement, or if you hear an unusual “clicking” noise) you should book a visit with your doctor who will examine you, prescribe new X-rays, a blood test, and in some cases, a bone scan. He will then decide if you need a so-called “revision” i.e. the replacement of some or all of the components with new ones. Problems with a hip replacement are normally due to an infection, overuse or injury – however, it is worth underlining that this happens only rarely.

Rehabilitation after surgery

Arthroscopic Debridement: you will be able to start walking with crutches immediately after the operation, and increase the amount of weight you put through your leg until you can walk unaided (2-3 weeks). You will have to do physiotherapy exercises initially to stop your muscles wasting and to get your hip moving again, and then as you recover, build up your muscle strength and stability.

Bone marrow stimulation procedures: you will be in hospital for 2-4 days after the operation, and will have to walk with crutches for about 6 weeks – gradually increasing the amount of weight you put through your leg. You will have to do physiotherapy exercises initially to stop your muscles wasting and to get your hip moving again, and then as you recover, build up your muscle strength and stability.

Hip Replacement: you will be in hospital for 1-2 weeks after surgery. During this time a physiotherapist will have shown you what movements you can and can’t do, and how to perform ordinary activities safely. You will also be given exercises to start moving your hip immediately, and then, once you have left hospital, you will have to follow a physiotherapy programme to rebuild your muscles and regain hip functionality. You will need to walk with crutches for the first 6 weeks, gradually increasing the amount of weight you put on the operated leg. You will also have to sleep with a pillow between your legs for the first month, and use a raised toilet seat for 2 months.

Hemiarthroplasty: you will be in hospital for 4-7 days after the operation, and you will need to walk with crutches for the first 4-6 weeks You will start physiotherapy immediately after the operation, initially to learn how to do simple activities safely. Once you are at home, you will follow a physiotherapy programme to rebuild your leg and hip muscles, regain your range of movement and develop your balance and the control of your hip.

Femoral Resurfacing: you will be in hospital for 4-6 days after the operation and you will need to walk with crutches for the first 6 weeks, moderating the amount of weight you put through your hip. You will start physiotherapy immediately after the operation, initially to learn how to do simple activities safely, and to start moving your leg. Once you are at home, you will follow a physiotherapy programme to rebuild your leg and hip muscles, regain your range of movement and develop your balance and the control of your hip.